A Secular Pilgrim Rides the “Camino de Velo” Copyright P. Marsh

After witnessing the arrival of the 10th-placed sailor in the Vendee Globe Round the World Yacht Race in February, I continued my N-S bike journey along France’s Atlantic coast. In icy weather, I passed through historic ports, oyster farms and ditches that drain this low-lying region. Catching the car ferry across the Gironde, the wide estuary downstream from Bordeaux, I entered a completely new landform–the never-ending sandy coastal plain of the Landes.

I rode for three full days on back roads or an isolated narrow tarmac trail regularly marked by signs as the “Velodyssey” route. The scenery was pretty monotonous: just endless pine forest, the beach resorts all boarded up, with only an occasional country village and church. The one hill went over the back of the biggest sand dune in Europe.

Of course it was below freezing at night, so I pedalled steadily for most of the day to stay warm and reach the bottom left corner of France and the hostel in Biarritz. It took about an hour to find, until I saw signs posted in French and Basque. Here I was welcomed and informed it had been hot the previous week. I was greeted by snow flurries the next morning, so had no doubts about staying for three days–relaxing, sightseeing and waiting for the weather to improve.

When the forecast suggested that spring had sprung, I finally set off along the scenic rocky coastline—on the most southerly road in France. After about 30 kms passing small ancient harbors, I realized I had turned the corner between SW France and NW Spain and was now going west.

I crossed the border at a small river—though I didn’t realize it until I saw the change in language on the street signs. The BASQUE style of architecture was well-established and I enjoyed seeing the wide variety of colors and patterns.

A Beginner’s guide to the Basque Country

In fact, I was now at the heart of the Basque country, which is officially bi-lingual for street and highway signs on both sides of the border. But as I rode west in Spain, the signs in Basque became more prominent and in the center of town the Basque had top billing over Castillian! I judged that Basque was as utterly inscrutable to a typical Spaniard as it was to me. The only feature I could recognize was the use of TX in place names, (It looks exotic but only sounds like a “ZZZhhh.”) Police cars are labeled ERTZAINTZA.

I noticed I was passing over and under a very modern narrow-gauge electric train line that runs along the coast, and began to wonder if it might come in handy later on……Other traditions I noticed were the fine houses that had a remarkable half-timbered look and many of the old men who wore a wide flat beret. This entire corner of Europe has a wonderful tradition of house design with external wood framing that is very distinctive, and extends to farms, town halls etc. Every apartment block has a unique look in outline, color and materials.

After a delightful detour on a road cut into the rocky shore, I arrived at the fabulous central plaza and town hall in San Sebastian (Donostia in Basque). My homework paid off and this time I found the hostel without directions. The man at the front desk looked at my passport, but only had one question: Was I a pilgrim? I decided I fit the bill, agreed I was, and was given a large discount on my bill.

Thus I began to understand the place of “The Camino de Santiago” (the Way of St. James) in this region. It’s been bringing visitors here since around 1000, which must make it the greatest piece of vacation marketing in history. (On the web I learned that an incredible 200,000 people walked the official 800 kms route in 2011.) I was happy to learn that there was a coastal option to the high-altitude route popular in the summer, because there was snow on the hills behind the coast from the French border all the way west through Bilbao, and Gijon.

While riding the Camino del Norte in Spain, the author came across a remarkable bike sculpture in Cabezón de la Sal in Cantabria.

The next day there were ancient port towns all along the route, and two stretches of extreme climbing, one signed “2 kms at 10%.” The second one climbed right up to the snow line, which showed me the snow was really there at around 1,000′. A recurring sight was the number of sporting cyclists riding hard on the only east-west route: a very busy two-lane road. It was sometimes horrendously noisy for cycling—but that didn’t seem to concern the literally hundreds of would-be racers out for training sessions.

That was all I could manage in a day, and when it got dark I was still 15 miles from Bilbao. I looked around for a secluded spot to camp and realized the geography of the entire region–all hills and valleys–was going to be against me. I cruised into a new garage under construction and was surprised to spot a car wash that offered a very good roof, if nothing else.

It was noisy of course, but looked like the best bet. I slumped off the bike, and sat down on my rolled-up mattress to see how I felt about stopping there. . When it started to rain, I was definitely convinced! I slept well, but you will be relieved to know I managed to find a proper dwelling for the remaining 10 days.

The next day, the road went up and through four tunnels beneath the summits, which avoided even more climbing, then made a steep descent into Bilbao, which is situated in a narrow valley like all Basque towns. I rode downhill across a striking red suspension bridge across the city’s river and had a stunning view down to the equally striking Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao–a world famous cultural landmark. Bilbao is the capital of the Basque culture with the language appearing first on most signs and the buses carrying the curious title of “BILBO BUS.”

Bilbao’s Crowning Glory?

This controversial structure dominates the city center and cost lots of local money in the mid-90s when the economy was strong. From the outside it is a huge piece of random/abstract design with no rhyme or reason. Nonetheless, it gleams on the riverbank, commanding attention. From the inside, it is equally abstract, with strangely-shaped halls jutting out at odd angles from a tall inspiring glass-covered central atrium looking like a temple to the arts.

This controversial structure dominates the city center and cost lots of local money in the mid-90s when the economy was strong. From the outside it is a huge piece of random/abstract design with no rhyme or reason. Nonetheless, it gleams on the riverbank, commanding attention. From the inside, it is equally abstract, with strangely-shaped halls jutting out at odd angles from a tall inspiring glass-covered central atrium looking like a temple to the arts.

As for the art inside, it barely registered against the vastness of the bizarre shape of the interior and there was no attempt to use the central hall to display art—no sculptures, mobiles, or murals. It was really more like a railway station than a gallery. So, I spent more time watching a Gehry bio-documentary than I did looking at the art…

What I learned was that the talented Mr Gehry can sketch a new building’s outline in 10 seconds on paper, or model it in 10 minutes with cardboard, scissors and tape. He and his team of hot-shot architectural lackeys sit around all day like kids on a craft project, cutting and sticking pieces of card together. The customer gets whichever one Frank doesn’t throw in the bin by the end of the week. That’s why they look like something a kid assembled…

I had wondered about this when I saw Gehry’s rock and roll museum in Seattle, and Bilbao is so much more extreme that it caused me to seriously consider what these buildings say about the arts and civic pride? I judge Gehry’s talent is not as an architect but a ruthless self-promoter–of his completely dysfunctional buildings.

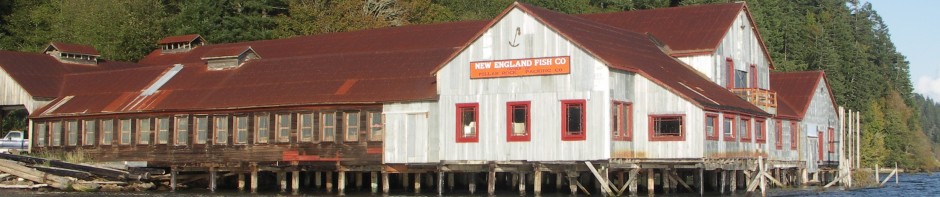

Consider that he will never design any building intended for serious use–like a college, apartment block, research center because they have a bottom line—they have to function, while a museum can be anything you want—like the freezer rooms of an old cannery that happen to work very well for the fishing/cannery museum that I manage in Astoria! (Incidentally, London’s biggest newest art museum is a huge empty power station that will soon have a modern addition, making it as impressive as anything Gehry can ever imagine.)

From Astoria to Asturias

Both the hostels I stayed in were busy all night with party-goers and no sign of pilgrims, so after a day off, I set out again with renewed energy to the mouth of the river, which I crossed on the world’s oldest operating transporter bridge built 1893—a wonderful mode of travel that I had overlooked all my life!

Soon, I reached the next province of Asturias where I imagined Spanish reigned supreme. It was on this leg that I began to catch on to the chain of pilgrim refuges about a day’s walk apart. My first stay was in a real lodging house run by Benedictine nuns. It cost 15 euros but was very quiet and I slept well. There was also a bike shop a block away where I found a single high pressure 20″ (BMX) tire to replace the second one I had worn through….I have definitely learned to always carry a spare tire.

There are many fabulous beaches along the Cantabrian coast, and I often had great ocean views. I reached the widest inlet where I caught a foot ferry for a satisfying boat ride across to Santander–a stylish popular resort city for the well-to-do British since Victorian times. I had identified a hostel there by searching on the web using the wi-fi in the hostels in Bilbao.

The tourist office pointed it out nearby, and luckily this turned out to be within 2 blocks of the bus and train stations, and the ferry office. This was very useful, as it allowed me to confirm that bikes were welcomed on the local trains, and check the date that the ferry to Portsmouth departed.

So my general plan was to follow the coast and the pilgrim trail by road west until it turned inland, then catch the train back to the Santander-Southampton ferry. This would give me a satisfying triangular route home with no need to unpack, fold and carry the Bike Friday. With a fairly clear goal, I set off for another day on the bike with plenty of hills to make me work. By evening, it looked like rain, so I decided to follow an arrow pointing to a pilgrim hostel down by the shore.

I found a small beach resort with a church right on the waterfront. Here I was directed to the side door where an old lady appeared to be the maintenance chief, as she was organizing a painting party inside. She led me up the hill at a brisk rate to her porch, where I signed in and was given the key to the shelter and paid my five euro fee.

I wandered along the coast road trying to remember her directions until I found an old school. The skies opened up as I let myself in and found one large dormitory full of bunks in what must have formerly been the classroom. I couldn’t remember where I saw the last store, and I wasn’t carrying much food. But I emptied my food bag onto the kitchen table and managed to put together a basic dinner and breakfast with the ingredients.

The church lady arrived at 9 am to make sure the place was tidy when I left. I guessed that she considered keeping the shelter tidy and the travelers inline was part of her religious duty. From here on, I managed to find and stay in more refuges, by using the provincial map of the camino, and paying attention to the dozens of small signs that marked the pilgrim coastal walking route.

When I reached Gijon, the fourth and last big city on the coast, I had to stop on the descent to admire another building of epic proportions—the University Laboral. It was a long way to the harbor and the tourist office, where I was commended for noticing the town’s name in the Asturian language….. XIXON!

They sent me back the way I came to the municipal student hostel housed In a genuine XVII century palace. It had been artistically enlarged with a modern addition,but there was no doubt about the old walls, which were about two feet thick. Lest you doubt, here is a picture. I dropped off some excess luggage at the bus station to hopefully increase my speed a little, and enjoyed another two days of ups and downs into tiny harbors on the zig-zagging coast road.

In the next two refuges, I met a German walker, then a Polish walker, and on the last day finally eased up faced with a powerful headwind. Crossing the freeway bridge into Galicia—which also has its own Celtic language—I had to lean hard to the left to keep my balance. I found myself in a group of seven in a very small modern refuge building beside the estuary, including the young German who had caught up with me, like the tortoise and the hare!

That proved to be a very poor night’s sleep, suggesting to me how crowded the refuges are in the summer! The camino leaves the coast here and looks much more pleasant, away from the growth and bustle on the coast, so I hoped the walkers would enjoy being off the road for long distances. But I was glad to be catching the train back the way I had come—especially with the strong west wind bringing rainstorms. I gladly paid the low fare and sat back in the little (narrow gauge) carriage to review the route in comfort back to Gijon.

I checked the departure time for the next morning and found there was only one train –at 8.30 am– to get me back to Santander and the weekly ferry to England. I returned to the palacio hostel in pouring rain, which continued for the next 30 hours. I had a day to spare and was determined to tour the vast “eclectic-neoclassical” university campus despite the weather. It was stunning and just about worth the soaking, but meant I had to dry a lot of clothes before the morning…

That evening I had a unique opportunity to hang out with the students in the hostel watching fabulous Barcelona FC and the great Argentine Lionel Messi play the Italian champions in the Euro Cup ¼ finals on TV. The Spaniards played their standard tip-tap quick passing game for about an hour before their opponents finally cracked and made mistakes in defense.

The next morning I had to leave early for the station and got a cold surprise: the rain was turning to snow, giving me a chilly ride at 7.30 am in the dark on, sleet, and on a very confusing road system. The train station was full of commuters watching the departure sign anxiously as all the lines inland were blocked! But the ticket clerk made a phone call and sold me a ticket east because the coastal line was supposedly still open……..

Miraculously, the train set off. Outside the town, the countryside was blanketed with snow and the mountains looked magnificent. The train crashed into frozen trees leaning over the tracks, and we all changed to a new train several times before leaving the snow behind and arriving in Santander about five hours later. Even the ferry was delayed out at sea, so I took a cold ride along the esplanade and spent all my remaining euros filling my food bag for the next 24 hours.

We departed at 10 pm, and I slept fairly well on the floor of the quiet room. We arrived in Portsmouth 24 hours later, and I ended up on the last train to London, reaching Waterloo Station at 12.30 am. At 1am, I found myself biking along the Thames embankment, which was lit up like a Christmas tree in the city center. Realizing the path was wandering away from the direct route, I took to the back streets in Rotherhithe, arriving home in Greenwich at 2 am on the 31st day of the tour.